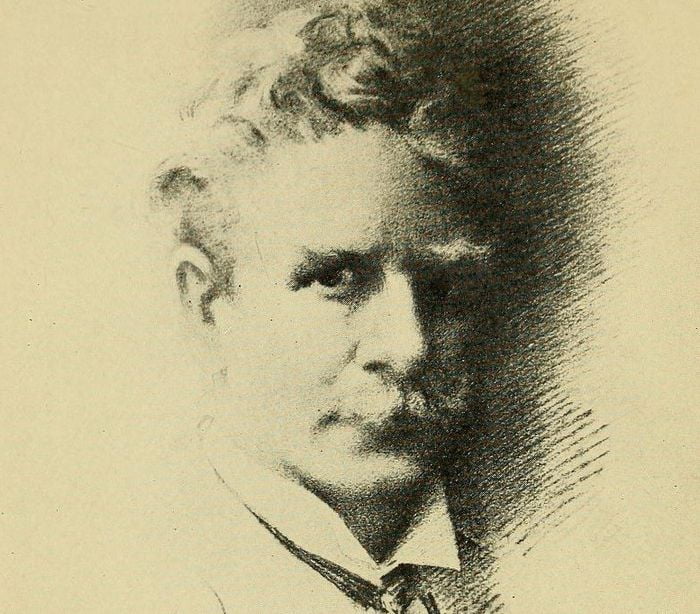

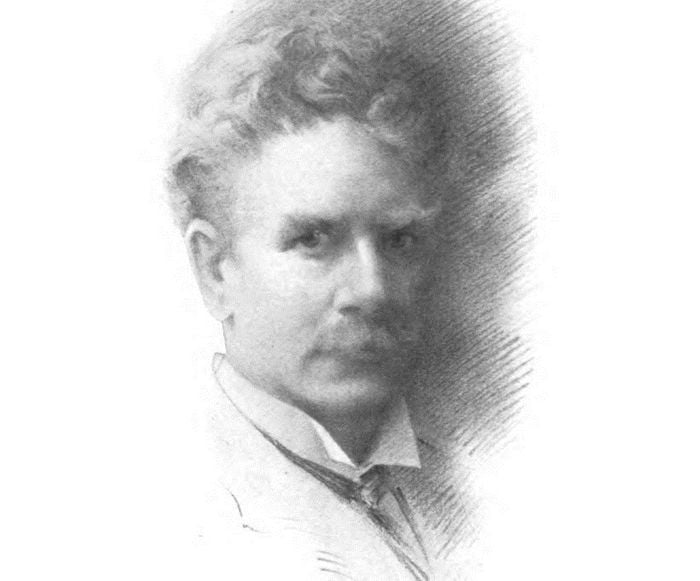

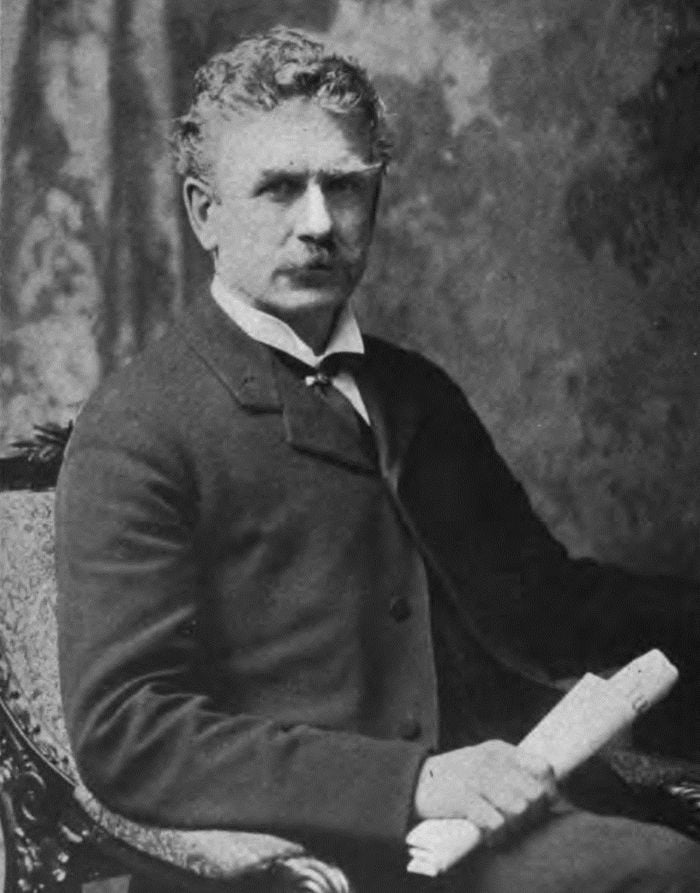

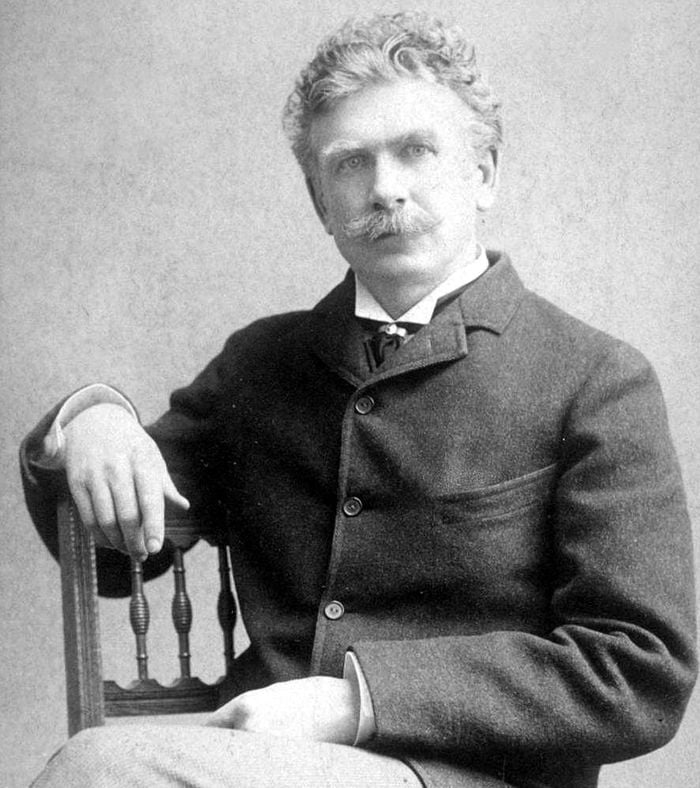

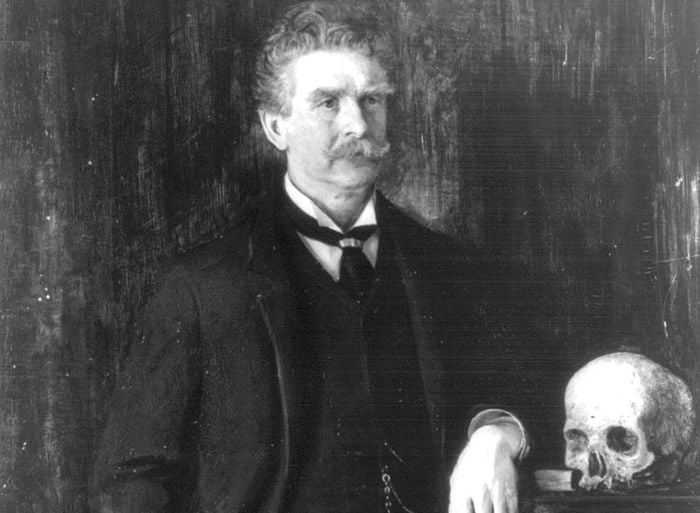

The Man and the Snake – Ambrose Bierce (1839-1914)

Bierce was born in Ohio in 1839. He served as an officer in the Civil War, and in 1866 went to California, six years later proceeding to England.

Before that time he had begun to write those brief sketches and stories which have only in recent years become widely known. Between 1877 and 1884, having returned to California, he edited a magazine. He was last heard of in Mexico in 1914, and is supposed to have died there that year. Bierce’s stories are remarkable achievements. They are highly finished psychological studies cast in fiction form, of a tragic or satirical turn.

The story of The Man and the Snake was published in the volume m Tales of Soldiers and Civilians. Copyright, i8gi, by E. L. G. Steele. Reprinted by permission of Chatto and Windus, who include it in a volume entitled In the Midst of Life.

The Man and the Snake

From Tales of Soldiers and Civilians

It is of veritably report, and attested of so many that there be now of wise and learned none to gainsay it, that ye serpent his eye hath a magnetic properties that whoso fillet into its suasion is drawn forwards in despyte of his wile, and perished miserably by ye creature his byte.

Stretched at ease upon a sofa, in gown and slippers, Harker Brayton smiled as he read the foregoing sentence in old Morryster’s “Marvells of Science.” “The only marvel in the matter,” he said to himself, “is that the wise and learned in Morryster’s day should have believed such nonsense as is rejected by most of even the ignorant in ours.”

A train of reflection followed—for Brayton was a man of thought and he unconsciously lowered his book without altering the direction of his eyes. As soon as the volume had gone below the line of sight, something in an obscure corner of the room recalled his attention to his surroundings. What he saw, in the shadow under his lied, were two small points of light, apparently about an inch apart. They might have been reflections of the gas jet above him, in metal nail heads; he gave them but little thought and resumed his reading. A moment later something—some impulse which it did not occur to him to analyze—impelled him to lower the book again and seek for what he saw before. The points of light were still there. They seemed to have become brighter than before, shining with a greenish luster which he had not at first observed. He thought, too, that they might have moved a trifle—were somewhat nearer.